About

Contents

IntroductionHow the DSS Works

How the DSS can be Used to Help Prioritise Biodiversity 'Outcomes'

Summary

Authorship and Acknowledgements

Introduction

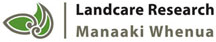

Vertebrate pest control (VPC) in New Zealand is necessary to protect native flora and fauna, and to protect people from the damage that pests cause to agriculture and property. Deciding how to control vertebrate pests has become increasingly complex over the last 20 years due to new knowledge of pest impacts and control, an increase in the range of products available for pest control, new legislative and safety requirements for pest control operations1, increased public interest in the impacts and control of pests, diversification of the pest control ‘industry’, and reorganisation of the roles of some of the key participants (Fig.1).

This Decision Support System has therefore been developed to assist a wide range of possible end-users in determining the most appropriate choices of control tools for a particular pest control programme.

Disclaimer: The advice presented by the DSS has been developed by integrating information, from diverse sources, that was considered to be accurate and reliable. However, Landcare Research accepts no liability for any errors or omissions or loss or damage suffered, either directly or indirectly, as a result of relying on or using the information presented through the DSS.

1 The National Possum Control Agencies (NPCA) has produced booklets that summarise: ‘legislation surrounding vertebrate pest control’ and ‘minimum requirements for safe use and handling of vertebrate toxic agents’

Figure 1.

How the Decision Support System Works

The DSS was designed by identifying the ‘generic’ questions that arise when pest managers are considering the most appropriate choice of control method, and using ‘yes/no’ responses to determine the decision paths followed. Such an approach is intuitively easy to understand, and unambiguous. The questions are focussed around the key issues of: operational aims, land tenure, farming practice, public and environmental safety, community views and involvement, and landowner views. Consideration of these potential constraints in a logical and systematic way results in a series of recommended options being presented that are then further narrowed down by establishing what control methods may have been used previously (as frequently repeated use of most methods results in declining effectiveness), and basing final recommendations on the basis of the likely cost of the remaining suggested methods. The relative humaneness of control tools is not considered in the decision paths because the use of inhumane control methods is regulated by the Agricultural Chemicals and Veterinary Medicines Act with regard to vertebrate toxic agents (i.e. poisons), and the Animal Welfare Act (with regard to traps). Additionally, many kill-traps have been evaluated against a NAWAC standard for killing-performance.

Recommended methods are linked, in most cases, to best-practice advice based largely on documents produced by the Department of Conservation and by the National Possum Control Agencies (NPCA). Most of the best practice advice is well-supported by NZ-based research findings, for which references are given.

The system therefore emulates the decision-making process that an experienced, well-informed pest manager would typically follow. However, the tool is designed to support, not replace, decision-making by pest managers. This is because there is always the possibility that the DSS may not consider every operational constraint that applies to a particular pest control operation in a particular locality.

The DSS guides the selection of appropriate control methods, but it is not a comprehensive planning tool for pest control operations. Links to additional planning tools are however given in the ‘help’ sections associated with various parts of the DSS.

How the DSS Can be Used to Help Prioritise Biodiversity ‘Outcomes’

Biodiversity is the variation of life forms within a given ecosystem, ecological zone, or on the entire Earth. . Internationally, major efforts are being made to conserve biodiversity through the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Decade on Biodiversity, with New Zealand participating through The New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy which is being coordinated by the Department of Conservation.

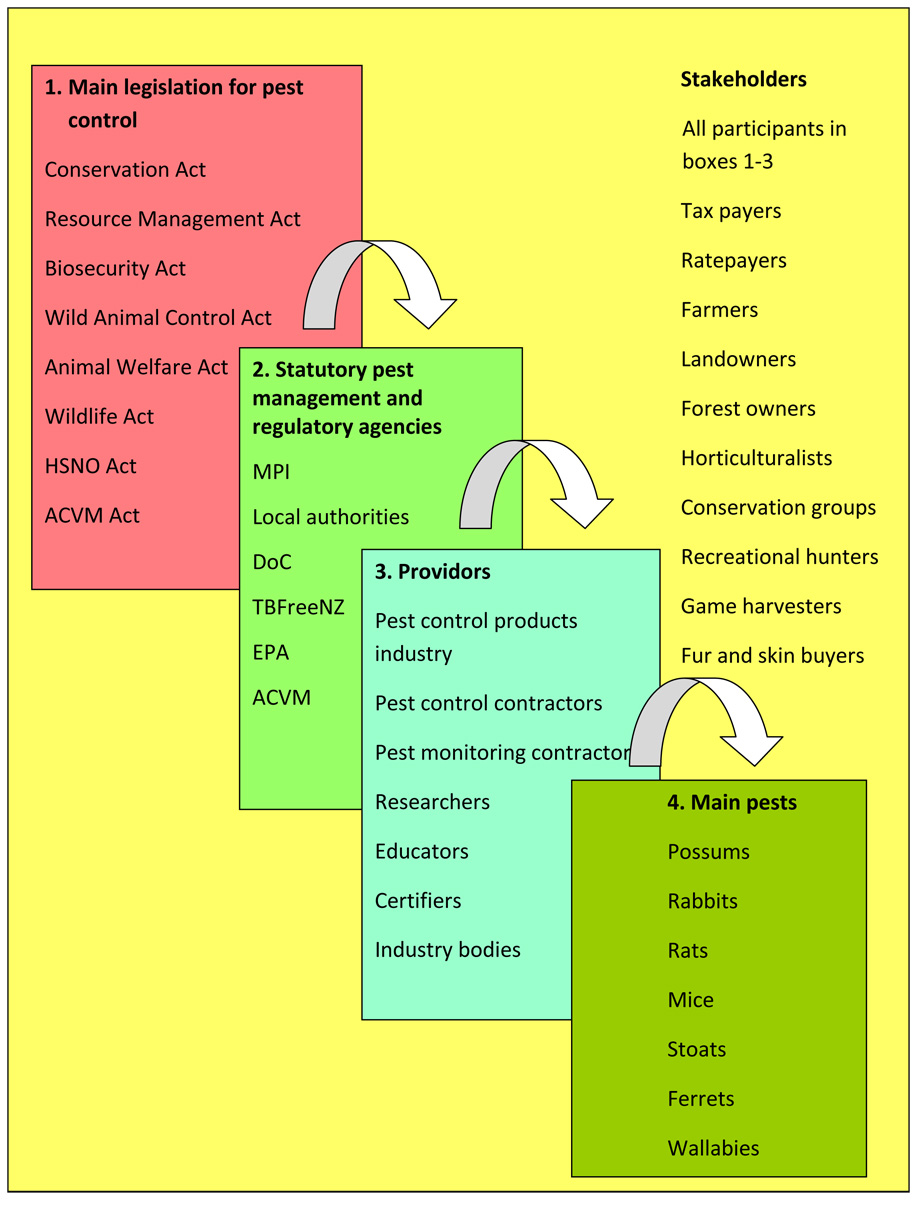

Managing biodiversity, at all levels from global to very localised, entails a series of common steps that are summarised in the flowchart below (Fig.2). The starting point is to define some generic goals (i.e. ‘high-level’ concepts). For example, DOC has identified six biodiversity management goals:

- Secure species from extinction

- Long-term recovery of threatened species

- Create a best minimum set of ecosystems

- Maximise ecological diversity and stability

- Protect and enhance ecosystem services

- Increase community participation

Smaller organisations with a localised focus may have much narrower and more specific goals such as restoring the fuchsia canopy in a local reserve, or increasing the population of fernbirds in a wetland to a specified target.

Goals are therefore focussed on the biodiversity assets (e.g. species, sites, or habitat types) that an organisation wants to manage, and information about these is obtained through existing knowledge (e.g. databases) or by ‘inventory monitoring’. Once the assets have been identified and their status assessed, through monitoring if necessary, it is then possible to establish the outcomes that are considered both desirable and achievable by some form of management. In turn, this means that the present ‘threats’ to the assets must be identified so that an appropriate type of management can be planned. In New Zealand, the threats to biodiversity are commonly pests, but other threats such as habitat loss through deforestation or drainage may need addressing.

The DSS is a tool that can be used where pests have been identified as a threat. As well as predicting the most appropriate pest control methods for specified circumstances, the DSS incorporates a conceptually simple generic means of prioritising proposed biodiversity management projects . While this provides for a transparent process, the quality of the result is dependent on the reliability of the information that the user supplies for the four input parameters used to estimate the relative efficiency of a project:

Relative efficiency = (Weighting x Benefit x Success)/Cost

These parameters should be used to reflect the goals of the biodiversity programme in terms of the intrinsic value of assets (i.e. ‘weighting’), the difference to the assets expected from a proposed project (‘benefit’), and the probability of success. New information or new methodologies may be needed to improve estimation of these parameters. However, the DSS includes a module (presently for possums only) to enable costing of all methods of proposed control.

This process will provide pest managers with a consistent and transparent means of assessing the relative efficiency of proposed operations. Those with the highest efficiency rankings can then be selected to get the ‘best bangs for bucks’ from limited budgets.

To enable ongoing improvement of biodiversity management, monitoring can be conducted at two levels. Firstly, ‘output monitoring’ of the pest reduction achieved may be needed (i) to progressively refine estimates of some of the above parameters, and (ii) as a basis for payment of pest control contractors. Secondly, ‘outcome monitoring’ of the improvement in biodiversity asset enables the organisation to assess the progress being made towards the biodiversity goals.

Figure 2.

Summary

The DSS will:

- identify the most appropriate control options in response to proposed operational details and constraints

- provide transparency/accountability in decision-making by producing a hard copy summary of the DSS input and output

- enable prioritisation of pest control operations alongside other biodiversity ‘actions’ such as fencing or revegetation

- provide for a consistent approach nationwide amongst pest managers considering all the key constraints when selecting pest control methods

- present ‘best current practice’ for all control methods to maximise effectiveness and minimise risks

Authorship and Acknowledgements

The DSS was designed and developed by Dave Morgan, Margaret Watts, and Bruce Warburton of Landcare Research, Lincoln.

The work was funded by an Envirolink ‘Tools’ grant from the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology. The Department of Conservation, Animal Health Board and NPCA are gratefully acknowledged for generously contributing information to this development. Richard Bowman perceived the need for the DSS and we are grateful for his assistance throughout its development; Julian Carver is thanked for facilitating workshops during this development; Richard Maloney generously contributed ideas on the ‘prioritisation’ component. We are grateful to the publishers of the many publically-available documents we were able to source on the internet.

v 1.0.0.1010